This post contains affiliate links. This means that if you make a purchase through one of these links I will get a small commission at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products and services to readers that I really believe are valuable.

A Compelling Case for Personal Experimentation and Learning Broadly

I remember how focused on music I was when I attended college in the late 90s. I recall thinking to myself that I was going to become the absolute best musician I could become (amazing!) and that nothing else in the world mattered.

True to this mindset, I’d often cut corners on basic self-care needs such as diet, sleep, and exercise. I allowed relationships to suffer. This was done dutifully in service to my all encompassing passion.🙄 I came to define myself wholly as a musician, a consummate specialist in the world of musical expertise, or at least that was my aim.

Was this a good thing? To so narrow my field of interest that I could hardly be bothered with you know….doing regular people things, all so I could attain some feeling of having “arrived” at my own imagined level of desired expertise?

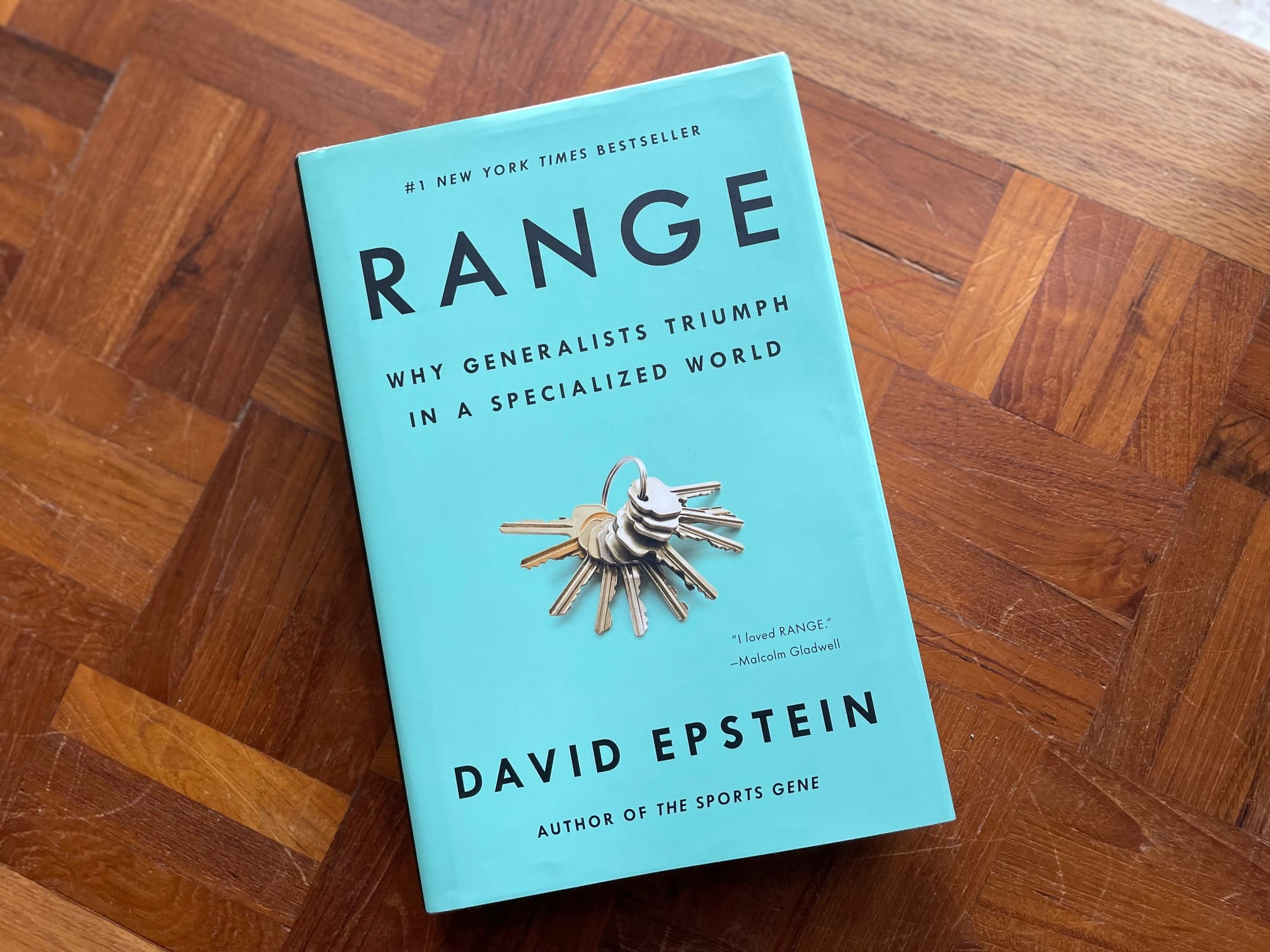

Eh. Somewhat. The premise of David Epstein’s book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, is that contrary to society’s favored story of the hyper-specialized person who reaches success due to their singular focus, most highly successful people’s stories do not follow this model. Rather, many world-class experts indulged various interests and explored several fields, eventually finding success not in spite of their meandering paths, but because of them.

I think it benefited me to focus for a while and acquire a baseline of expertise in a single discipline. After having built a certain kind of clarity in a single field, it becomes easier to draw parallels to concepts and ideas in other fields, closely related or otherwise. Even so, I wasn’t as specialized as some.

I didn’t begin playing music until age 10, and although I never reached the sort of world-class level of mastery that examples in the book like Tiger Woods and Roger Federer did, I did get good enough to work as a musician professionally. Luckily, I’d eventually break out of my own self-imposed navel-gazing constraints to experience much else of what the world has to offer. If you find yourself in the opposite sort of position, drifting from one interest or job to another and you’re starting to feel left behind in life, you might appreciate what the author has to say in this book.

Generalists Thrive in Complex, Unpredictable Situations

“Above all else, the mentat must be a generalist, not a specialist.”

The Mentat Handbook, Children of Dune

Lately, I’ve been reading the later books in Frank Herbert’s sci-fi saga, Dune. In the future world of Dune, mentats are an order of humans, similar to a guild, which serve to replace the benefits of computers, such as computational thinking and statistical analysis of multiple, broad, overlapping factors. A single mentat works for one of the Great Houses, which rule over entire planets. This one person has to take in a multitude of data, make solid conclusions based on it, and that can in turn have ramifications that influence millions of people.

David Epstein’s book is solidly grounded in the non-fantastical real world. It makes the case that people who have experience in a number of different areas (generalists) have some advantage(s) over those with deep expertise in a single field (specialists). This is the case even as many career fields insist that their professionals get ever more and more hyper-specialized. This can cause those specialists to miss new ideas or connections to other fields which would have been beneficial.

According to Epstein and the research he’s done, it is essential from young childhood through adulthood, for individuals to try many different activities and experiences, something called sampling. How do you choose an instrument or sport for your child when you don’t even know what they’ll be good at? The answer is to let them try lots of different things and if they decide they don’t like an activity, be willing to let them move on.

This shouldn’t be viewed as wasted time, but rather valuable experience as they take what they’ve learned, what they liked, and what they didn’t like along with them to the next activity they try. One of the problems is that we as adults, tend to view sampling as wasted effort not just for our kids, but for ourselves as well.

One of the things that makes this book so engaging is the sheer number of examples given, in which an individual applied knowledge from one area they studied to a completely different area. Oftentimes they not only achieved success, but they did so in novel and unexpected ways. Examples include the writer Patrick Rothfuss, who though having given up being a chemical engineer, still managed to apply some of that chemistry knowledge to deepen and strengthen his best-selling novel The Name of the Wind. A fantasy novel.😯

From Jordan Peele and Lin Manuel Miranda to Charles Darwin, Van Gough, and the non-fiction filmmaker Sebastian Junger, Range is filled with individuals who experimented with different subjects and mediums, synthesized their experiences, and formulated something new and exciting from them. They often arrived at their success by meandering around, trying a bit of this and a bit of that. While on the surface, that might sound like a lack of stick-to-it-ness, it’s really just people trying things out and upon realizing an activity doesn’t suit them, pivoting to something more optimal.

Learning Across Disciplines

“Space between practice sessions creates the hardness that enhances learning.”

David Epstein, Range

The book also builds upon a lot of the most well-known ideas out there in regards to learning and achieving success. There are references to the 10,000 hour rule made popular in Malcom Gladwell’s book, Outliers. There’s a section on spaced learning (distributed practice) which does a great job of illustrating why the best way to retain information long-term is to study it in an inefficient way in the short-term by taking breaks in between trying to recall information. In this case, “space between practice sessions creates the hardness that enhances learning.”

As well, there’s an interesting take on goal setting by Y Combinator cofounder Paul Graham. Here, he offers an alternative to the idea of working backwards from a goal, making a plan and sticking to it. He instead offers that we should “work forward from promising situations” in order to leave ourselves with the best possible range of options.

These sections serve to further the point that the world is getting more dynamic and complex and those who will be successful in the future will be the ones that are best equipped to deal with the unknown, unforeseen, and ambiguous situations that arise. These individuals will have a broad set of experiences and knowledge of multiple disciplines from which to draw upon.

Final Thoughts and Rating

Lest, any person feel that they have wasted time on a failed career or hobby they ended up not being very good at, Range seems to be telling us that if we are open to it, all of our experiences add up to a grand education of life. They are not wasted time. They continue to inform us in our next endeavor and the ones after that.

It could just be that I feel justified in reading this book that the insatiable curiosity that’s crept up in my thoughts the past 10 years or so is all the better. But, irrespective of my own account, Range by David Epstein continues to make waves even now, four years after its initial publication. If nothing else, it’s thought provoking and highly engaging nature should satisfy you if you’re interested in the fields of learning, productivity, and self-improvement.